If the doors and windows are locked, try the keyhole

Martin Dunne is a human givens therapist living in County Kildare, Ireland, with a private practice in nearby Carlow. He has an MA in human givens psychotherapy from Nottingham Trent University and is a human givens supervisor. He gives one-day workshops on aspects of the human givens approach to interested organisations and groups.

Martin Dunne describes his work with a young woman with anorexia who did not want to address the problem.

This is exactly how it happened. The phone rang and a woman spoke in a rapid, anxious voice. “Is that Martin? You have to help – you were recommended. I have a 19-year-old daughter, Ashling, who is in a very bad state. She has recently been discharged from a psychiatric hospital, but she has started to self-harm again. She has been diagnosed with personality disorder; she has also been diagnosed with anorexia and is starving herself to death. She is a bright girl with lots of potential, but she is throwing her life away. Will you see her as soon as possible, please? She has agreed to see you.” I said yes.

My practice is situated in a busy medium-sized building where a variety of other professionals work. There is an attractive, comfortable reception area where one can meet the clients. This is perfect for me because the three-minute walk from the reception area to my room gives me the chance to start rapport building with a new client before we even get there. “So you found us okay?” “You travelled from such and such a place, didn’t you? “There’s a beautiful old church there, isn’t there?” and so on and so on, all questions that, without their noticing, invite agreement and cooperation. However, 10 minutes before the time set for Ashling’s appointment, there was a knock on the office door. I opened it and standing there was a young woman, tall, incredibly pale, and frighteningly thin.

“Are you Martin?”

“Yes. And you must be Ashling,” I deduced. She nodded, walked in and, still wearing her coat, sat down. Then she fixed her eyes on me. “So. What do you do, then?”

“How do you mean?” I replied, somewhat taken aback.

“I have been to psychiatrists all over this country. I have been in hospitals. I have taken the medications and nothing has changed since I was 12 years old. And, to tell you the truth, I am tired out by the whole lot of you. So. What do you do? What’s different about you?”

This had never happened to me before and I was, all of a sudden, uneasy. My usual routine of gently building rapport before information gathering, etc, etc, had gone out the window. I was being interviewed about what I could do to help this young woman. What I read in her eyes was, did I want the job or not? Get on with it.

I began to explain myself. “Well, the first thing I do is listen to your story and try to ascertain which of your essential emotional needs are met or unmet. We have an emotional need, for example, for security. When we feel under threat for whatever reason, or the environment in which we live feels unsafe, then we suffer distress…” I went on, briefly explaining each of the emotional needs and the consequences when they’re unmet. Suddenly, she got up, removed her coat, sat down again and said, “All right. I’ll stay”. It was then that I noticed her wrists and arms. There were deep purple and red cut marks, looking just as it would look if someone had gouged great lumps of wood out of a plank with a chisel.

unmet. We have an emotional need, for example, for security. When we feel under threat for whatever reason, or the environment in which we live feels unsafe, then we suffer distress…” I went on, briefly explaining each of the emotional needs and the consequences when they’re unmet. Suddenly, she got up, removed her coat, sat down again and said, “All right. I’ll stay”. It was then that I noticed her wrists and arms. There were deep purple and red cut marks, looking just as it would look if someone had gouged great lumps of wood out of a plank with a chisel.

I offered her some water and took some myself. (I think I needed it more than she did.) Then I said, “I want to thank you, Ashling.”

“For what?”

“For making it here today and for interviewing me. I am not sure if I get the job, so shall we say that this can be the probation period and see how we get on?”

“Sounds good to me,” she said, and she laughed. Ashling lived at home with her mother and father and three younger brothers. She wanted to go to art college, but couldn’t get down to work on her portfolio because of a recent onset of anxiety and depression. This had been triggered by splitting up with her boyfriend and worsened by the ensuing rows at home over her not wanting to get out of bed. Her early school days had been unhappy and this, she pointed out, was where the trouble had started. When she was seven or eight, she had been bullied by her school teacher for being slow at maths; he regularly made her stand in front of the class and humiliated her. This treatment had a knock-on effect because, soon afterwards, some of the other girls at the school began to tease and bully her. She reacted instantly to this – each day, before school, she became physically sick and dreaded going. Her parents complained to the school but nothing was ever done about the teasing and bullying. By the age of 12 she had lost all confidence, was purging food and self-harming, and withdrew into long periods of silence and depression. She lost the few friends she had and became very isolated.

Early on in the session, I asked her favourite place to relax and she said her garden, when the sun shone. She said her garden was the only place where she felt there were no demands made of her. Nature just did its own thing throughout the year, regardless, and that made her feel free. (This piece of information was to prove highly significant much later, in building a viable strategy for moving forward in our work.) Ashling’s goals for the therapy were to compile a portfolio for art college entrance, to get a handle on the anxiety and depression and to stop self-harming: these were the things that she found overwhelming and wanted to make a start on sorting out. We fleshed out what she would be doing if these were no longer a problem.

No-go area

As she hadn’t mentioned food, I raised it, asking what she would eat during the day; she declined to reply. She was insistent that this was a no-go area and that she did not want to talk about it. So I decided not to pursue the topic any further at this time. For me, the most important thing was to get the ball rolling with what was presented. As we know, when a client speaks about the enormity of their problems, those problems can seem and feel overwhelming to them. If, as therapists, we can make a judgement call on what is the most pressing part of the presenting problem and address it, then the bigger problem reduces in size – as in the old “How do you eat an elephant?” “In small chunks.”

In this session, we looked at how our brains respond to our environment and I introduced the 7:11 breathing technique for calming down – albeit with some difficulty, because Ashling’s concentration was erratic. Still, although she found it hard going, she persisted and began to feel its good effects. This persistence, I told her, was a great resource and would be of significant benefit in our work together.

Before ending the session with relaxation and guided imagery, I wanted us to talk about a strategy for our next session. Her much-loved garden at home, I thought, offered an appropriate metaphor: I suggested that, before she could enjoy the flowerbeds or the roses, some clearing and preparation had had to have taken place first. I explained the rewind detraumatisation technique, telling her this powerful technique had the capacity to take a still disturbing memory/pattern and turn it back into an ordinary, albeit never pleasant, memory of something that was in the past. I told her how effective many clients with similar histories and experiences had found it, and then suggested that the rewind might act as the preparation, or heavy lifting, part of our next session. Thereafter, having left off past worries and troubles, she could better appreciate the ‘freedom’ she so prized.

She said, “Getting rid of the bad stuff first and then enjoying the nice bits later on.”

“Exactly.”

Her chosen location for the guided imagery at the end of the session was a beautiful magic garden, full of artists from history all doing their own thing.

The utilisation principle

I reflected after the session that, while we don’t want to normalise human suffering, it is helpful to normalise the symptoms, and also people’s attempts to understand suffering, through our understanding and knowledge of what it is to be a human being. The utilisation process, as defined by renowned American psychiatrist Milton Erickson and emphasised in the human givens approach, encourages the therapist to use everything that the client brings to therapy, including negative things, in order to move forward. I see it as a two-way process, which involves bringing all the life experience, knowledge and coping strategies from one’s own life as a therapist to the table, as a means of maintaining rapport and working in a collaborative way. Finding the metaphor that works for our clients is part of that process, because metaphor is the key to the gate through which we enter their lives. As I have known artists all my life (there have been many in my own family), I felt I had some understanding of their temperament – the sense of isolation or separation they often experience, a kind of ‘artistic anomie’ that may feed into their metaphors for life. Metaphors may be based on an endless list of personal narratives, tempered through the lens of our unique image and construction of self and our place in the world that we inhabit and share with others. Working in, and through, our client’s metaphors means searching for solutions within them, thus enabling clients to own their own progress and change.

The surf board

At the start of the second session, Ashling reported only two episodes of self-harming in the fortnight since I saw her last; it was usually an everyday occurrence. She had managed to handle the overwhelming feelings of sadness, which up till then had resulted in self-harming. Asked how she had achieved this, she said, “The surf board”.

At the start of the second session, Ashling reported only two episodes of self-harming in the fortnight since I saw her last; it was usually an everyday occurrence. She had managed to handle the overwhelming feelings of sadness, which up till then had resulted in self-harming. Asked how she had achieved this, she said, “The surf board”.

“What surf board?” I asked.

“You said, if feelings become intense, imagine you’re on a surf board, feeling the intensity of the waves and going with them, staying above them. You said they will subside in time, as long as you stay on board.”

I didn’t recall this but it was an image I had remembered finding useful¹ and I must have incorporated it into a story that I had come up with in our guided imagery. Ashling seemed a little more relaxed, although her sleep had been erratic throughout the week. As planned, we carried out the rewind technique for the experiences of being bullied by the school teacher and by her fellow pupils. I checked with her that she had watched the images go by at speed without being drawn into them, and she reported that she had and that some were frightening at the beginning but less so as the film got faster. Ashling was very tired by this time, and we agreed to meet two weeks later.

Utilising her love of art, I asked her in the intervening period to go to the National Gallery of Ireland to see Irish artist William Leech’s most famous painting, A Convent Garden in Brittany, and to sit for a half an hour in front of it. I asked her to do this for two reasons. First, the gallery was in Dublin, an hour’s train ride away, and she would be obliged to spend around four hours there, before she could get a train back. This would provide an excellent way to get her out connecting in the world again. Second, the painting, showing young novices at prayer, evokes a sense of calm and beauty. She agreed to the task.

Then the lapse

The phone rang at 11pm, two days before Ashling’s next appointment. It was Ashling’s mother and she was very upset.

“She has been in her room all day and will not come out or even talk to me. I don’t know what to do. I’m afraid she will do herself harm, because this is how it always happens. I thought she was fine yesterday, after her appointment with the psychiatrist. I thought she was getting better, but now we’re back at square one again.”

I tried to calm her, saying, “This takes time; we need to be patient.” After a while, I asked her to inquire whether Ashling would speak to me. She went upstairs and I could hear her outside the bedroom calling out, “Ashling? It’s Martin. He wants to know if you’ll speak to him.” She returned to tell me that Ashling had said she would ring me back in a few minutes.

Twenty minutes later my phone rang again. “I’ve blown it!” said Ashling. “I’ve made a mess of everything and Mum doesn’t understand. I’ve cut myself again and I’ve had a terrible day.” I reminded her of how far she had come on her journey, and asked if she could see me the next day. After some time, she agreed to come to the office.

The next day Ashling arrived as promised, sat in the chair, and the words came tumbling out. “You probably think I’m awful, as well, and I don’t blame you. I went to see the psychiatrist yesterday and I felt he got angry and told me I must attend to this anorexic behaviour once and for all, and then he finished the appointment. I felt angry because I thought I was doing well. Then, on top of that, I had arranged to meet an old boyfriend for coffee. I sat there for nearly an hour and he didn’t turn up. So, I went home and that sadness came back at me and over me – and I cut myself.” She showed me the marks.

There was a pause; I have learned over my time as a human givens therapist that it is not always necessary to fill every silence with noise, that not every pause in a conversation means that someone should speak, so I left the silence to do its own job. In that silence, I thought back over many years to a time when I felt powerless. The most uplifting and strengthening thing a friend had said to me then was, “You should be so proud of all you’ve achieved against a tide of setbacks.” So I repeated that sentence to Ashling. She looked up at me. “What have I to be proud of?”

“Do you know that, in all the work you’ve done, you’ve had only one tiny lapse, one tiny slip, one small hiccup out of all that effort?” I explained the process of change, lapse, and relapse: that any such lapse into old behaviours should be seen for what it is – temporary, a short slip, a setback, a one-off; it didn’t have to signify full-blown relapse – unless she chose to make it so (thus giving her control over what happened). In other words, all was far from lost and the occasion could be a ‘learning experience’.¹ As I went on, I could see she understood. Even physically the blood began to return to her face, just as if she had been given a transfusion.

“You’re right! It was only a setback, a one-off, wasn’t it?”

“Like falling from a horse.”

We ended the session by talking about the meaning of William Leech’s wonderful recreation of a peaceful convent garden at a time when Europe was preparing to go to war, and Irish workers, on starvation wages and suffering great humiliations, were preparing for the Irish General Strike of 1913. Despite all of this, Leech had created a beautiful work, showing that, even in the darkest of times, a beautiful and tranquil world co-existed.

The difficult phase

Two weeks after I had last seen her, Ashling reported that she had not engaged in physical self-harm and had begun to draw again, which she found relaxing. I congratulated her, asking how she had managed it. She reported that she felt more in control of her feelings and moods. (When we had done an emotional needs audit in a previous session, the need for control/autonomy had stood out as needing bolstering.) This change, she agreed, was significant.

Deciding to take advantage of the positive momentum, I said, “And how are you rating your eating now?” This did not go down well. She immediately became angry and insisted that she did not want to discuss it. As maintaining rapport is vital in any session, I said, “Imagine if these roles were reversed and I came to you and said, ‘Ashling, you have helped me to stop harming myself; you have helped me with my confidence; I am beginning to see daylight; oh, and I have a big problem with food and eating and I don’t want to discuss it’. Would you say I was being reasonable?” She looked down for a moment, then said, “No”.

Ashling was by then calm again, so, to maintain a neutral stance, rather than focus directly on anorexia, I asked what relationship she thought she had with food. By introducing the idea of a relationship with food, I was hoping to move her into her observing self. She frowned and looked away. “I have experienced the reasoned arguments and the emotional arguments,” she said. “The psychiatrists have tried punishment and anger; my family have tried cajoling. But, do you know what? I’ve rejected it all. I just don’t like food. It makes me ill even thinking about it.” This was her model of reality at this time. And once again she made it clear that the conversation was over.

was hoping to move her into her observing self. She frowned and looked away. “I have experienced the reasoned arguments and the emotional arguments,” she said. “The psychiatrists have tried punishment and anger; my family have tried cajoling. But, do you know what? I’ve rejected it all. I just don’t like food. It makes me ill even thinking about it.” This was her model of reality at this time. And once again she made it clear that the conversation was over.

Tim Bond, in his book Standards and Ethics for Counselling in Action,² suggests asking the following question in cases such as this one: “Whose dilemma is this? Is it yours or the client’s?” I thought about this now. Was it her or my dilemma if my client chose to starve herself, even after receiving advice on where to seek medical help? It could be said that it was her dilemma, especially if she even refused to address the issue with me. I could have said to myself, “I’ve done all I can and she is just not receptive to any further change”, and called a halt to our work. (I think this dilemma fits with psychologist Leon Festinger’s theory of ‘cognitive dissonance’,³ which holds that, most of the time, we’ll do whatever it takes to get rid of conflicting uncomfortable beliefs or values, in order to keep our positive self-beliefs intact – achieving it, in this case, by shifting responsibility for lack of change back to the client.)

But the human givens approach enables us to come at this from a wider perspective. It takes account of the fact that the client’s model of reality, through which they see and make sense of their world, is likely to be skewed by their heightened state of emotional arousal. Thus the aim is to try to find an imaginative way to reduce that arousal – and continue with the therapy. I very much wanted to continue with Ashling. I sought supervision on this case and my supervisor gave me sound advice. While approving the work I had done so far, he was adamant that I needed not to be afraid to get onto the subject of food. Otherwise, it would be a bit like working with someone who is smoking and drinking heavily, helping them to give up smoking but ignoring, at their request, the heavy drinking. At some point, continuing with the one was likely to lead to a resumption of the other, undoing all the good. That confirmed me in my knowledge that anorexia was a major and very pressing problem to Ashling’s overall wellbeing. I couldn’t just step back.

Somebody once said to me on the topic of problem-solving, “If the front door is locked, try the back door; and, if the back door is closed, try a window; and, if the windows are sealed, then try getting in through the key hole. But do keep trying.” So I did. Trying something different I brought a resource from my own past experience. Many years ago I attended an acting workshop while training as a drama therapist. The theme of the workshop was method acting (devised by the Russian theatre director Constantin Stanislavski and later refined by Lee Strasberg in the US) and it concentrated on how to build a character from the outside in; for example, taking a character in a play and finding out what life was like for someone like that. It might mean spending time with homeless people or people with early dementia, or researching what a particular type of person did for a living, what books or newspapers they read, and so on, and from there building a real living person with a lifestyle and a past, present and future. Wear his coat, we were told. Walk the streets he would walk – become him instead of just going on stage and delivering dialogue. However, what was more interesting to me was the aspect of this work known as sense memory:⁴ it was about looking at the internal world of the character, his emotional life. How did he feel about different situations? How might he react? In this particular part of the workshop, there was a focus on how different everyday foods might generate different emotional responses. For example, soup might produce a nice feeling of being warm and cosy and secure. Remembering drinking soup might help an actor reproduce, in a live performance, the sense of his character feeling warm, cosy and secure, thereby adding to the authenticity of the portrayal. I decided to use this experience to review Ashling’s attitude to food. What she had told me was that she had a very strong emotional reaction to food. She had said nothing about being compelled to diet, or thinking she was fat, or associating thinness with aspirations to become a model or get a boyfriend – just that even thinking about food made her feel ill. And therein, I realised, might possibly lie a solution.

Summer fruit

Ashling arrived for her next session feeling very positive. She had not engaged in self-harm, had made good inroads on her art portfolio and was sleeping much better. I congratulated her and said how I admired her ability to be creative and flexible, and that these two gifts were a great asset in overcoming any obstacle. I told her I had this idea that I had never tried before and asked if she’d be willing to engage in an experiment. She agreed to give it a try.

I asked her to close her eyes and recall a beautiful day in her garden, in a long hot summer with all the roses in bloom and their scent wafting on the breeze. I took my time and, when she was deeply involved in the imagery and starting to smile to herself, I asked her to imagine a piece of food that seemed so right to eat in that lazy hot summer. Her face softened, and she replied, as if tasting them, “Strawberries”. I asked how they felt in her mouth. “Beautiful and soft,” she said. I moved on, creating a picture of autumn, asking the same question, and this time she recalled eating apples and the pleasant emotional memory associated with the season. For winter it was an orange (oranges are particularly associated with Christmas in Ireland), and, for springtime, she chose shelled nuts.

I asked her to close her eyes and recall a beautiful day in her garden, in a long hot summer with all the roses in bloom and their scent wafting on the breeze. I took my time and, when she was deeply involved in the imagery and starting to smile to herself, I asked her to imagine a piece of food that seemed so right to eat in that lazy hot summer. Her face softened, and she replied, as if tasting them, “Strawberries”. I asked how they felt in her mouth. “Beautiful and soft,” she said. I moved on, creating a picture of autumn, asking the same question, and this time she recalled eating apples and the pleasant emotional memory associated with the season. For winter it was an orange (oranges are particularly associated with Christmas in Ireland), and, for springtime, she chose shelled nuts.

“That was a beautiful experience,” Ashling said afterwards. “I never thought I could enjoy the simple pleasure of eating again.” We had now crossed a divide and could, for the first time, talk openly about food and, more importantly, connect positive emotional memories to food and eating. To reinforce what she had seen in her imagination by making a concrete representation of it, I drew on my whiteboard the fruits she had mentioned and asked her again to recall the seasons associated with each one. We then rehearsed this in guided imagery. At the end of this session she was cooperative, calm and very relaxed.

I gave her a homework task of finding some pictures that represented the seasons – physical pictures, photocopied from the library or spotted in magazines in newsagents – and to buy fruits of her choice on her way home. At home, she was to set up each picture in turn, close her eyes and recall the season before she ate the fruit. My hope was that the visual cue and the evoked good memory would let the food go down easily. I asked her to do this on three days before I next saw her and to keep a record about how she felt, and what thoughts occurred to her while doing this. She readily agreed.

In her next session she reported that she had carried out the task and was enjoyably surprised that the emotional memories around eating fruit linked to seasons of the year were all pleasant. She never once felt sick. Her anxiety had disappeared and she was working full-time on her portfolio.

I saw Ashling two weeks later and she was full of life. Not only had she taken to eating all the fruits together in a fruit salad but had added oats and was now making her own orange juice. Building on this success, I recommended Ashling see a friend of mine, a professional nutritionist who is familiar with the human givens approach, who was willing to work with her. I saw Ashling once more just to check that all was well, and progress was ongoing. She reported that she had seen the nutritionist and was on her way to living fully. And that was where our work ended.

What I think happened

Autobiographical memories are what create our personal meaning. As psychologist Gillian Cohen put it in her book, Memory in the Real World, “Our sense of identity or self-concept depends on being able to recollect our personal history.”⁵ Control of this narrative is essential for our security and place in the world. Ashling was humiliated at an early age by her teacher and by children she thought were her friends. Nothing came of her parents’ complaints, so she felt that no one was listening to her. The only control she felt she could exert was over her physical self, with all the unhealthy restrictions that ensued. But hers was an artistic temperament that needed freedom, and the one constant in her narrative was the natural cycle of the seasons, as witnessed in her garden. As she had said when we first met, “Nature just did its own thing throughout the year, regardless”, and that made her feel free. It was not associated with any demands, any bargaining. It just was. So recalling the seasons was an easy, unthreatening task and the introduction of food connected to that sense of not feeling threatened gave her the control to rewrite, or pull positives from, the narrative on her own terms, thereby making positive associations between food and her body’s ability to welcome it as essential nourishment.

I heard from Ashling’s mother about seven months later. Ashling is at art college, has a new boyfriend and continues to do well. The method I used may not be the conventional way of treating an eating difficulty – these are, on the whole, complex and sometimes require a suite of interventions from many sources. But the human givens approach allows the fluidity and flexibility to intervene at many levels of human emotion and behaviour, with the underlying proviso of doing no harm. Here’s to the Ashlings of this world – may they live long in emotional wellbeing.

References

1 Marlatt, G A and Donovan, D M (2005). Relapse Prevention: maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors. 2nd edition. The Guilford Press, New York, London.

2 Bond, T (2000). Standards and Ethics for Counselling in Action. 2nd edition. SAGE Publications Ltd, London.

3 Festinger, L (1957). A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance. Stanford University Press, California.

4 Carnicke, S M (1998, 2009). Stanislavsky in focus: an acting master for the 21st century. 2nd edition. Routledge, Oxon.

5 Cohen, G (1989). Memory in the Real World. Psychology Press, Hove, E Sussex.

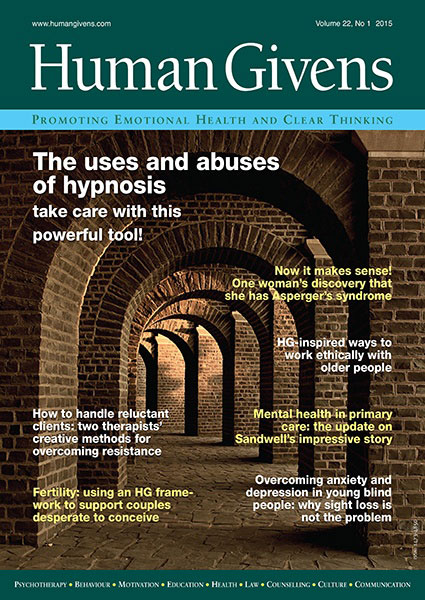

This article first appeared in the Human Givens Journal Vol 22, No. 1, 2017. Each issue of the Journal is jam-packed with thought-provoking articles, interviews, case histories, news, research findings, book reviews and more. In order to maintain its editorial independence, the journal doesn’t take advertising – which means it depends on new readers and subscribers. If you enjoy the articles on our websites, why not take out a subscription or buy a back issue today…

This article first appeared in the Human Givens Journal Vol 22, No. 1, 2017. Each issue of the Journal is jam-packed with thought-provoking articles, interviews, case histories, news, research findings, book reviews and more. In order to maintain its editorial independence, the journal doesn’t take advertising – which means it depends on new readers and subscribers. If you enjoy the articles on our websites, why not take out a subscription or buy a back issue today…

Learn More

- Advanced CPD for HG Therapists: Join Jo Baker for the Working with Eating Disorders One-Day Workshop

- Discover more resources and case histories on our Eating Disorder Awareness page

- Learn more about the human givens approach

- Find your nearest HG therapist here

- Our Ask the Expert mental health podcasts give you the chance to hear human givens professionals talking about mental health and emotional wellbeing from the point of view of their particular area of expertise.

HG’s ‘Ask the Expert’ Podcast Series

Working with anorexia – why we shouldn’t focus on food

– featuring Martin Dunne. Martin is a human givens therapist, he has a successful private practice in a dedicated, multi-disciplinary holistic clinic. Martin also has extensive experience in group and individual psychotherapy with young trainees in REHAB; and currently in Ireland’s largest addiction treatment centre. Martin has worked for over 10 years helping people overcome trauma, addiction and eating disorders.