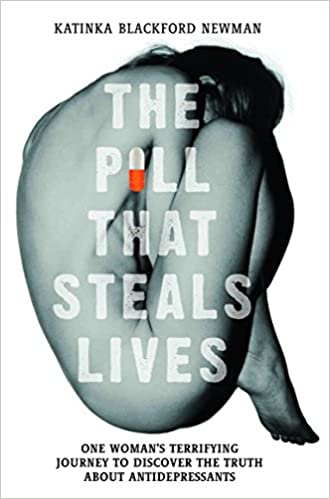

A review of The Pill That Steals Lives by Katinka Blackford Newman

Author of The Pill that Steals Lives: One Woman’s Terrifying Journey to Discover the Truth about Antidepressants, Katinka Blackford Newman is a documentary filmmaker from north-west London, but, as she tells us at the outset, it was not through her work that she discovered that antidepressants can steal lives. It was through terrifying personal experience. I found her story a compelling read – written in a personal, conversational and informal style and, at the same time, artfully weaving a huge amount of well-researched, important information into the context of her real-life experience. The result is a powerful, punchy, engaging and poignant story that we can all learn from.

In September 2012, Katinka, a previously fit, active, globetrotting career woman and mother, is 46, going through a divorce and facing having to sell the house that is the much-loved home of her children Lily, 11, and Oscar, 10. Highly upset at this prospect and experiencing insomnia, anxiety and distress, she sees her GP, who will not prescribe medication. The story might well have ended there, and she would have been none the wiser about the harm that antidepressants can wreak. However, she seeks out a private psychiatrist, who diagnoses depression, prescribes two antidepressants and tells her to come back in a week.

Within hours of first taking the medication, Katinka develops severe mental and physical agitation (akathisia) and psychosis. Within three days she is hallucinating wildly and believes she has killed her children – but has no recollection of slashing her own arm with a knife. (In retrospect, she recognises and vividly describes experiencing the psychotic blurring of the dream state and waking state.) The confused and horrified reactions of her children and her bewildered estranged lawyer husband, family and friends make for uncomfortable reading. We can feel for them all as they try to deal as best they can with Katinka’s rapid descent into drug-induced toxic psychosis, whilst honestly believing and trusting that the doctors ‘know best’ and that, once she is admitted to the private psychiatric hospital three days later, they can get her better. What actually happened to her during her first stay at this hospital exposes complete professional ignorance of her dangerously toxic state.

After her discharge from inpatient care with a cocktail of drugs to keep taking, things go from bad to worse, to the point where she can’t look after herself, and needs carers, while her husband looks after the children. This goes on for a year and includes another six-week stay in the private hospital.

By September 2013, Katinka is deeply suicidal. “The feeling of wanting to kill yourself on these drugs is quite unlike the feelings of despair you might have without. … Like all of us I’ve had some pretty crap things happen in my life [including her father’s suicide when she was 12] but I’ve never ever wanted to end it all before. I’ve coped with all of them because there is always the hope that things are going to get better. … With drugs, it’s a different scenario. The feelings of inexplicable awfulness are inexorable. …You’ve been brainwashed into thinking you’ve got a disease and the drugs are making you better. … And there is no end. No hope. Nothing.”

It is when the medical insurance for private treatment runs out that she ends up, suicidal, at an NHS hospital where she is immediately sectioned and detained, rapidly taken off all medication – and experiences an extreme cold turkey withdrawal which, amazingly, she survives. Only a few weeks later, she is well enough to celebrate her 48th birthday at a dinner out with Lily and Oscar, close family and friends, and gradually rebuilds her relationships, reconnects with work, finalises the divorce and finds a new home.

It is at this time that Katinka begins trying to make sense of what had happened to her – and thus starts the next stage of her journey, detailed in the second half of the book. She discovers many stories of people having adverse reactions to antidepressants – and many cases where people have indeed killed themselves and/or others: “In every case of people who have killed on antidepressants it seems to follow the same pattern. They feel an inner restlessness and turmoil with a growing sense of dread. Often they can’t sit still. They keep hearing voices telling them what to do; they have thoughts of both suicide and killing others. [In the latter case] It ends with the person calmly ringing the police and confessing the crime, then showing no remorse until they come off the drug.”

Katinka decides this is a story that must be told and sets about making a TV documentary. In the course of this, she comes across, and recounts the work of, many people who have done much already to highlight the dangers of antidepressants, such as psychiatrists David Healy and Irving Kirsch, science writer Robert Whitaker, and Luke Montagu, one of the co-founders of the Council of Evidence-Based Psychiatry. She learns that the perpetrators of several particularly shocking murders and massacres were on antidepressants beforehand. For instance, psychiatrists who interviewed James Holmes (the ‘Batman killer’, who opened fire during a cinema showing of the latest film in Aurora, USA, killing 12 and injuring 70) believe he was in an antidepressant-induced psychosis, unable to distinguish between dreams and reality. Katinka herself is asked by a barrister to be a witness in the case of a 20-year-old student. Prescribed citalopram after breaking up with his girlfriend, he went home to his parents, who saw an unrecognisable individual, pacing constantly and crying, and then going out with a crowbar and viciously attacking a stranger. Fortunate enough to be seen by an expert who recognised that the drug had made him violent, he received a lesser charge.

The book even takes on the pace of a thriller as Katinka makes contact with a forensic medical investigator from Colorado who believes many people with bad reactions to antidepressants have a genetic mutation that makes them unable to process the drugs. She has a DNA test for it, which she offers Katinka. The possible ramifications of this within and beyond her family hit Katinka hard, as she waits desperately for her result.

The overwhelming message of this powerful book is that common antidepressant medications can have extremely harmful effects, especially on some unsuspecting people, causing excruciating agitation that can “flip a switch in your brain to make you do things you would never have dreamed of before”, including suicide, homicide and other normally unthinkably inhuman acts of violence. This effect has been known since the early 1990s but has been suppressed and played down by the pharmaceutical companies, whilst the unsuspecting public continues to take part in a “frightening human experiment”, which is having monstrous consequences in our society. As Katinka says, “With over 100 million worldwide taking antidepressants, there is no doubt that sometimes these pills save lives. But they also steal lives. Permanently. Not just a few, but it’s estimated many thousands around the world every year. And these are stolen lives that could so easily be saved if only people knew what the signs of drug toxicity are.”

I was left pondering the following questions. How does the blunting of feelings caused by antidepressants – particularly the widely reported loss of empathy and libido – show up in our regular psychotherapy work, affecting all-important relationship needs? Would I quickly spot signs of drug toxicity in a client (which could manifest as severe mental and physical agitation, bizarre beliefs, slurred speech, overwhelming alcohol and nicotine cravings, etc) and what should I do in such a situation? And what should I do when a client expresses or indicates feelings of the sort of drug-induced complete hopelessness and suicidality Katinka describes? These are not easy questions to answer and may perhaps, in time, have to exercise HGI’s ethics committee.

Katinka’s courageous and no-detail-spared account of her traumatic experiences, the impact on her close family and friends, and the equally terrifying stories of others should be a wake-up call for professionals (and their professional institutes and regulatory bodies) who prescribe these potentially lethal medications and continue to brush aside uncomfortable mounting evidence of their often catastrophic harm.

This review was written by campaigner and retired HG therapist, Marion Brown. You can listen to our Ask the Expert podcast, “Why Antidepressants Need to be Understood – with Marion Brown” here.

The Pill That Steals Lives: One Woman’s Terrifying Journey to Discover the Truth about Antidepressants by Katinka Blackford Newman was published by John Blake Publishing Ltd in 2016.